Article

ISO 8583: The language of credit cards

Martin Ek

Engineering

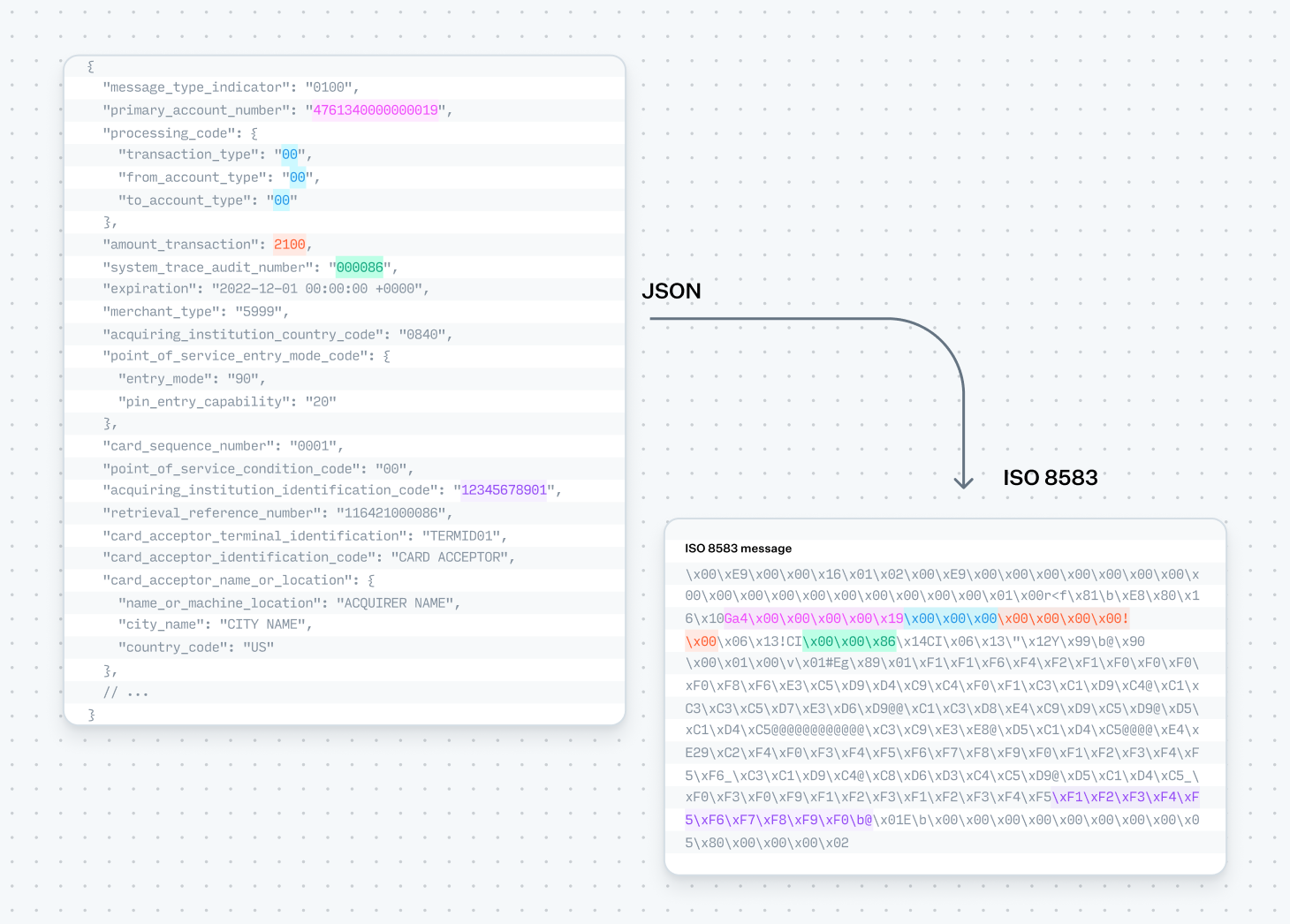

ISO 8583 is the standard for real-time messages communicated between acquirers and issuers through all of the major card networks. Whenever you tap your card at a point of sale device or click “purchase” online, odds are it will eventually end up as an ISO 8583 message sent between the merchant’s acquiring processor, the card network, and your bank’s issuer processor. Early on, the point of sale device or the ATM might have built and sent the ISO 8583 message directly to the acquirer, but in today’s ecommerce environment messages typically pass from the merchant to a payment processor in higher-level formats, such as JSON, which then in turn are translated to the card network’s ISO 8583-based format. This approach simplifies the process by abstracting away the complexity of the ISO 8583 format from the rest of the payments ecosystem.

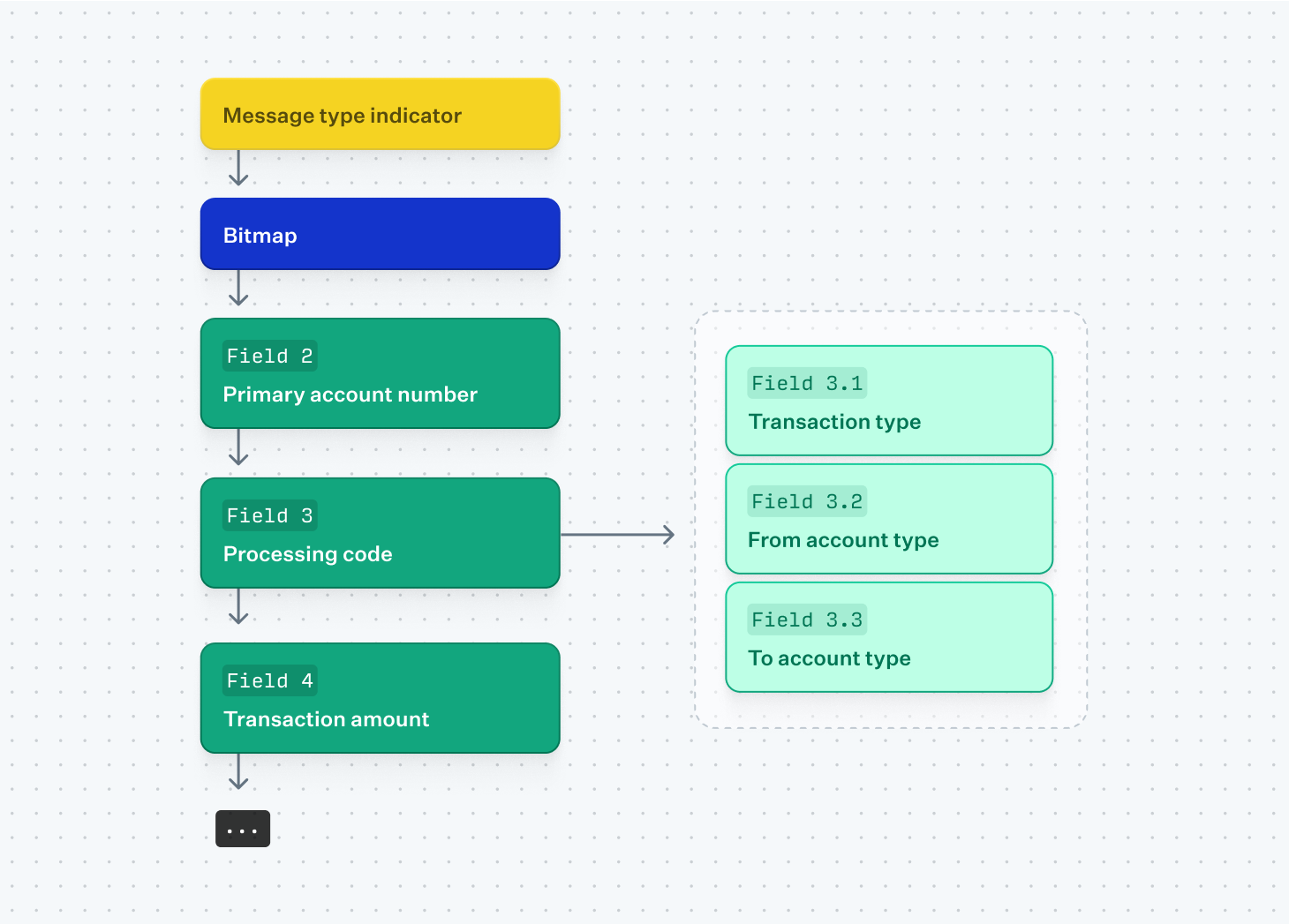

When the standard was first defined in 1987, it included the overall structure of the message specification and the names and lengths of the core fields, such as the card number (“primary account number”) in field 2 and the transaction amount in field 4. The message began with a 4-digit Message Type Indicator code representing whether it was an authorization message, a reversal, or some other message type. This was followed by a bitmap that told the recipient which fields were present. It left room for a few fields that could be used by networks to include network-specific information, and as a result the various card network specifications quickly diverged through a series of nested fields that did not overlap at all. Later versions of the standard greatly increased the number of fields, reducing the need for network-specific behavior for new implementations. Specifications like Visa’s Base I have thousands of clients running on everything from mainframes to devices like ATMs, however, making sweeping backwards incompatible changes next to impossible. As a result, these specifications still largely follow the rules set forth by the original standard from 1987.

The standard also allowed flexibility in how each field was serialized. For instance, networks could choose to use EBCDIC—the 8-bit encoding scheme favored by mainframes—for all fields, or opt for packed BCD to save space in numeric fields wherever possible. This made the specifications defined by each network, such as Visa, Mastercard, and Discover, eventually evolve to have more differences than similarities.

Throughout this article we’ll explore the basic structure of the ISO 8583 format before delving into its more complex nested sub-fields. In the end we’ll look at how you might define an ISO 8583 parser in code, grounded in how we process card transactions as an issuer processor connected directly to networks like VisaNet here at Increase.

When the standard was first defined in 1987, it included the overall structure of the message specification and the names and lengths of the core fields, such as the card number (“primary account number”) in field 2 and the transaction amount in field 4. The message began with a 4-digit Message Type Indicator code representing whether it was an authorization message, a reversal, or some other message type. This was followed by a bitmap that told the recipient which fields were present. It left room for a few fields that could be used by networks to include network-specific information, and as a result the various card network specifications quickly diverged through a series of nested fields that did not overlap at all. Later versions of the standard greatly increased the number of fields, reducing the need for network-specific behavior for new implementations. Specifications like Visa’s Base I have thousands of clients running on everything from mainframes to devices like ATMs, however, making sweeping backwards incompatible changes next to impossible. As a result, these specifications still largely follow the rules set forth by the original standard from 1987.

The standard also allowed flexibility in how each field was serialized. For instance, networks could choose to use EBCDIC—the 8-bit encoding scheme favored by mainframes—for all fields, or opt for packed BCD to save space in numeric fields wherever possible. This made the specifications defined by each network, such as Visa, Mastercard, and Discover, eventually evolve to have more differences than similarities.

Throughout this article we’ll explore the basic structure of the ISO 8583 format before delving into its more complex nested sub-fields. In the end we’ll look at how you might define an ISO 8583 parser in code, grounded in how we process card transactions as an issuer processor connected directly to networks like VisaNet here at Increase.

Basic format

ISO 8583 messages can only be transmitted and received by parties with a shared specification detailing exactly which fields are present and in what positions. ISO 8583 messages, similar to other storage-efficient formats and unlike a more verbose format like JSON, carry only values and no field names. A basic message contains a “message type indicator” describing what type of message is sent, a bitmap explaining which fields are present, and the fields themselves.

Message Type Indicator

The message type indicator is a four-digit code that informs the receiver of the type of message being sent, such as an authorization message or a reversal. This tells the recipient which fields to expect to be present and not present in the message. While the specification defines a standard set of values—e.g.,

0100 for an authorization request and 0110 for an authorization response—some networks deviate from these values and retain only the general concept. The way the indicator is serialized also varies between networks. Some networks use packed BCD to reduce its size to 2 bytes, while others use simpler formats like an ASCII or EBCDIC 4-byte value.Bitmap

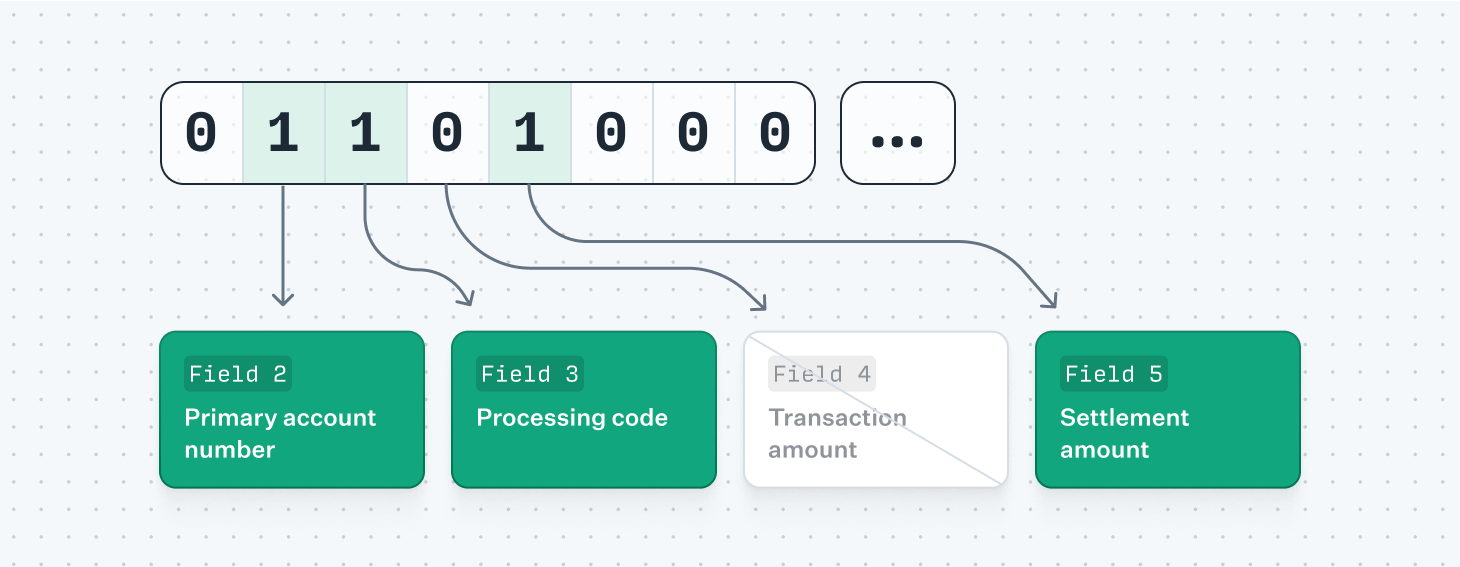

Most of the fields in an ISO 8583 message are optional, requiring the sender to convey which fields are present and which are missing. This is done with a bitmap, where each bit is set to 1 if the field is present and 0 if it is not. For example,

0110 1100 in the first byte of the bitmap communicate that fields 2, 3, 5, and 6 are present. The first bit in the first byte is reserved for communicating whether a second 8-byte bitmap is included, required when more than 64 fields are present. Similar to the Message Type Indicator, how the bitmap itself is serialized varies from network to network: hex, binary, ASCII, or EBCDIC are all possible choices.

Data elements

Following the bitmap, the sender serializes each present field in sequential order. Fields can be either primitive, containing a single value such as a string or an integer, or complex, containing nested fields within them. The serialization of primitive fields typically involves a combination of the factors enumerated below.

Encoding

Even for networks that prefer ASCII for their free-text fields, a serialized ISO 8583 message is usually not fully readable in plaintext, as the encoding of each field varies based on the type of field. There are generally a few options:

Encoding

Even for networks that prefer ASCII for their free-text fields, a serialized ISO 8583 message is usually not fully readable in plaintext, as the encoding of each field varies based on the type of field. There are generally a few options:

- EBCDIC or ASCII: Typically used for freeform text but sometimes preferred for all fields, regardless of content. Some networks support both EBCDIC and ASCII and translate between the formats according to their participants’ preferences. The major networks usually default to EBCDIC, as this was the encoding of choice for IBM mainframes when the networks were first built.

- Packed BCD: Often used for integers, with each digit occupying 4 bits. This encoding aligns with the 0-9 subset of hexadecimal, making it space-efficient for numerical data.

- Binary: Occasionally used for fixed length integers, encoded as 1 or 2 byte values in either little-endian or big-endian format, depending on the system’s requirements.

Variable or fixed length

A fixed length field always takes up the same number of bytes and padding is necessary to make sure the field fills its entire length. For example, amount fields are often 12 digits, right-justified, and padded with zeros—

How a variable length indicator is encoded also depends on the content of the field itself: a numeric Acquiring Institution ID might for example be encoded as packed BCD, where 12 digits is encoded in 6 bytes, but the length indicator would still state the number of digits, 12, and not the number of bytes, 6. This creates an interesting situation for odd-length integers. Take the number

A fixed length field always takes up the same number of bytes and padding is necessary to make sure the field fills its entire length. For example, amount fields are often 12 digits, right-justified, and padded with zeros—

000000002412 represents $24.12. Variable length fields are preceded by a length prefix, so no padding is necessary, as the receiver first decodes the length indicator and then uses that to know how many bytes to extract for the field itself.How a variable length indicator is encoded also depends on the content of the field itself: a numeric Acquiring Institution ID might for example be encoded as packed BCD, where 12 digits is encoded in 6 bytes, but the length indicator would still state the number of digits, 12, and not the number of bytes, 6. This creates an interesting situation for odd-length integers. Take the number

123 as an example: when serialized, it becomes the byte array [1, 35], represented in binary as 00000001 00100011. When we roundtrip this back, we end up with the value 0123 as we’re not able to differentiate between a 0 in the first nibble (half byte) and the padding-zero we used for 123. As such, it is necessary to incorporate the length indicator, which tells our encoder that the actual value length is supposed to be 3 digits so that we can trim away the first padding-zero.Nested messages

While the standard defines core fields such as “transaction amount” and “merchant identifier,” the list of pre-defined fields in the original standard eventually became a limiting factor for card network feature development. To address this, the standard reserved certain “private use” fields that card networks could utilize to serialize custom data as needed. This is where the specifications really started to differ between networks, both in the data they chose to communicate but also in how each nested field was serialized. The original standard provided limited guidance on this topic, an oversight that later versions sought to address.

There are generally three main ways to serialize a nested message:

There are generally three main ways to serialize a nested message:

- Tables: Each field is usually of fixed length and is always included, either with its actual value or replaced by a default placeholder value if empty.

- Nested bitmap messages: Only present fields are serialized, using a simplified, fixed-length version of the top-level bitmap to indicate field presence.

- Tag Length Value (TLV) messages: Each field is serialized as a tuple containing the field number ("tag"), the length of the field, and the field value. This format is defined by a separate standard, ISO 8825, which outlines the encoding rules from ASN.1.

How common each nested message type is varies from network to network. You might see American Express heavily use tables, while only Visa and China UnionPay make use of nested bitmap messages. Mastercard primarily sticks to Tag Length Value messages, a direction in which most of the card networks are slowly moving towards for all their new sub-fields.

Tables

The original nested message element is both the simplest and the most complex. In its simplest form, each sub-field is serialized sequentially, with no fields omitted, always resulting in a fixed number of bytes. This works fine for basic tables with a low number of fields but resulted in space inefficiencies for tables with a larger number of optional fields by having to send unnecessary padding characters for fields that were rarely present. Attempts to tweak the format to better support this and other scenarios introduced significant complexity, where the implementers would have likely been better off with a completely different sub-message type altogether.

This evolution reflects a common pattern in software development, where an implementation starts off as simple but gradually grows in complexity as extensions are added. In the end you’re left with a solution that is more complicated to implement for clients than what a new and separate concept altogether would have been.

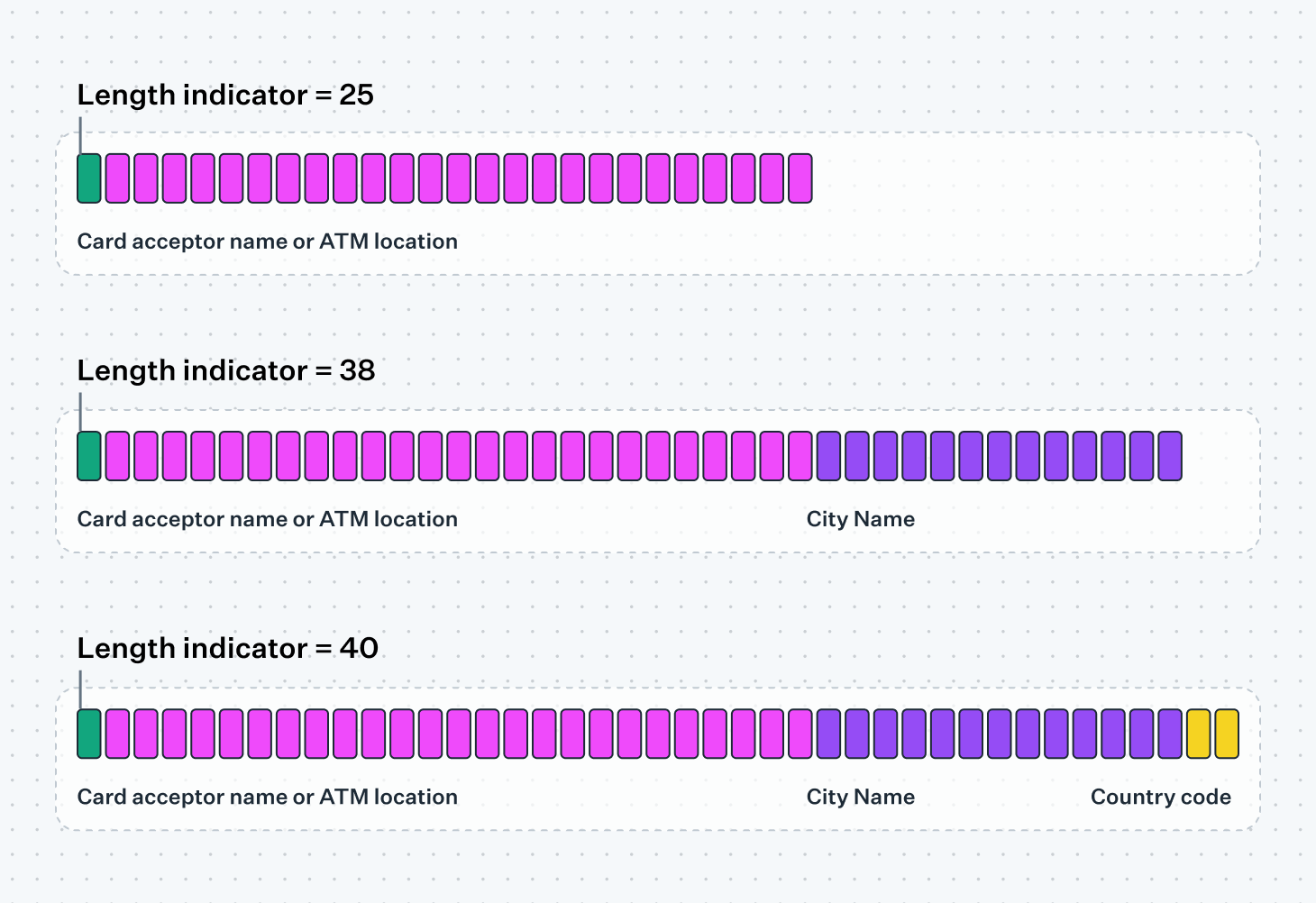

We can see the basic table format at display in one of the original fields, field 43 Card Acceptor[0] Name or Location:

This evolution reflects a common pattern in software development, where an implementation starts off as simple but gradually grows in complexity as extensions are added. In the end you’re left with a solution that is more complicated to implement for clients than what a new and separate concept altogether would have been.

We can see the basic table format at display in one of the original fields, field 43 Card Acceptor[0] Name or Location:

Variable tables

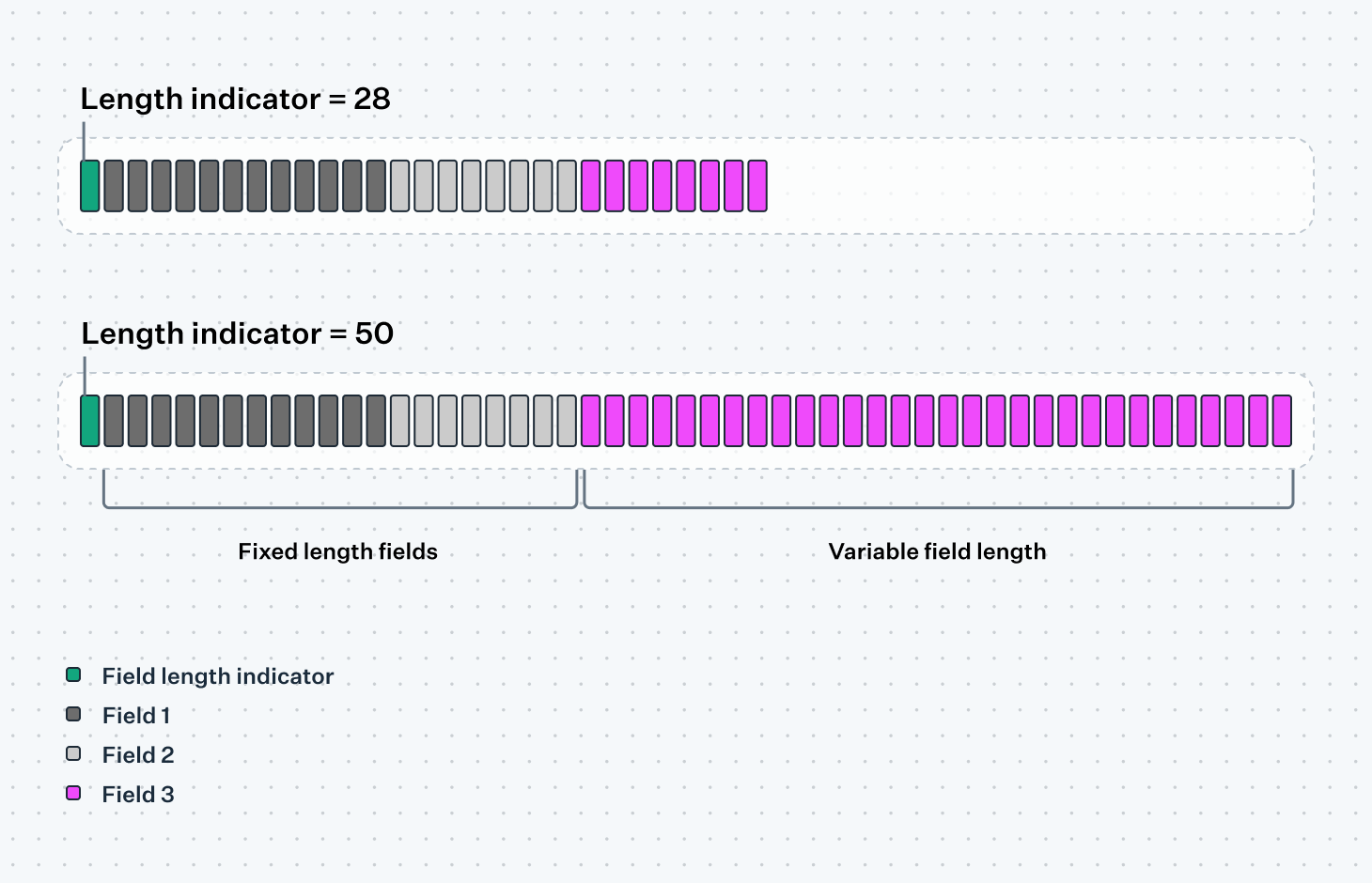

Each table takes up a predefined number of bytes and is always present, as receivers expect to parse each field in order. To omit the city name in the example above we would instead fill it with 13 spaces, resulting in the same overall size of 40 bytes. This is an inefficient approach if the city name is frequently omitted, forcing participants to transmit empty spaces to indicate the absence of data. Instead, in cases where a number of the sub-fields in a table are optional, implementations might let the sender omit sub-fields as long as they omit all the subsequent sub-fields in the table. Referring to the sub-fields in the example below as A, B, and C, you would be able to send the combinations of: only A, only A and B, or A, B, and C altogether. This type of “telescoping” is only possible when the table is preceded by a variable length indicator, communicating to the recipient how many bytes they should expect to read for the field, such as 25 bytes (A), 38 bytes (A + B), or 40 bytes (A + B + C).

Each table takes up a predefined number of bytes and is always present, as receivers expect to parse each field in order. To omit the city name in the example above we would instead fill it with 13 spaces, resulting in the same overall size of 40 bytes. This is an inefficient approach if the city name is frequently omitted, forcing participants to transmit empty spaces to indicate the absence of data. Instead, in cases where a number of the sub-fields in a table are optional, implementations might let the sender omit sub-fields as long as they omit all the subsequent sub-fields in the table. Referring to the sub-fields in the example below as A, B, and C, you would be able to send the combinations of: only A, only A and B, or A, B, and C altogether. This type of “telescoping” is only possible when the table is preceded by a variable length indicator, communicating to the recipient how many bytes they should expect to read for the field, such as 25 bytes (A), 38 bytes (A + B), or 40 bytes (A + B + C).

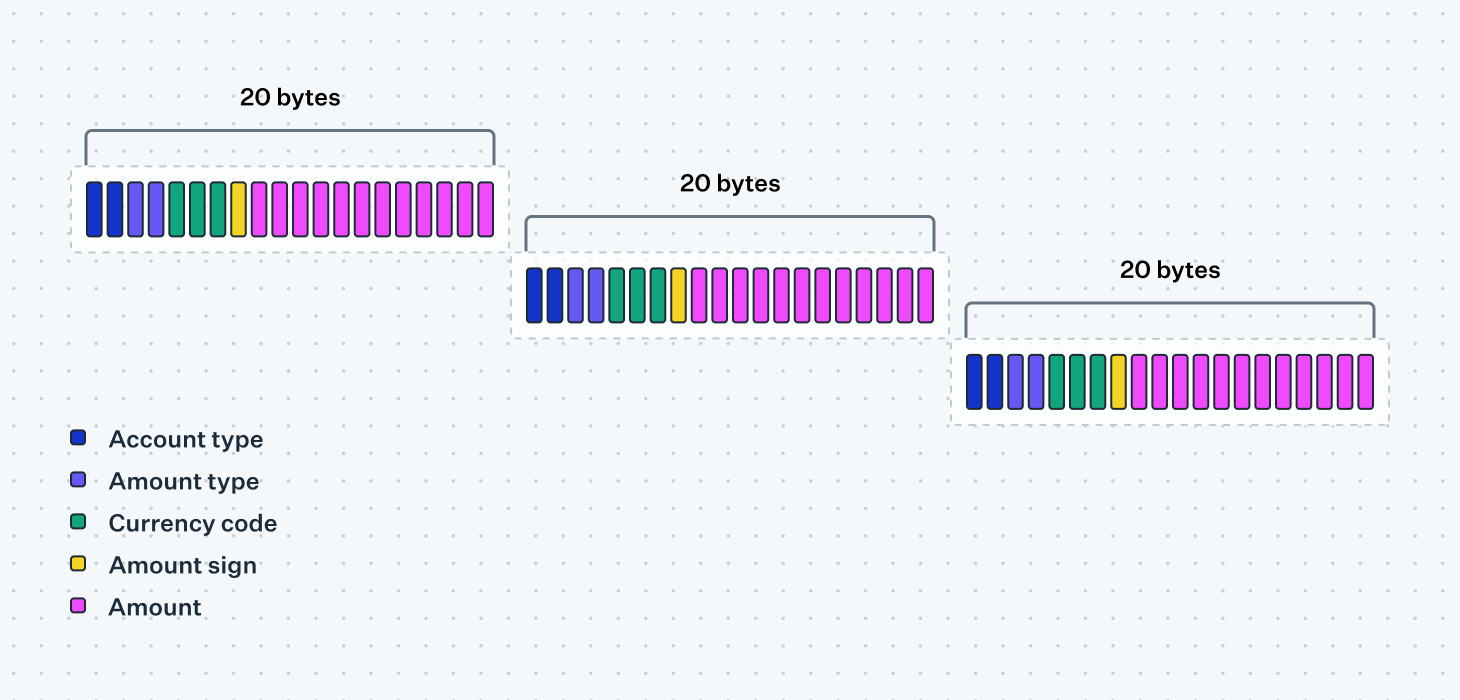

This concept is also used to nest sub-messages within sub-messages, as shown in the Additional Amounts field below, where we can serialize up to 6 additional amounts of 20 bytes each:

A similar extension happens when we want to support having one of the sub-fields take up a variable amount of space. Going back to our Card Acceptor Name or Location table, if we wanted to support a card acceptor name sub-field of up to 200 characters, the original approach would require all participants to pad the value with spaces up to the maximum length of 200 characters. This method, while functional, is inefficient for a standard that greatly values its frugal use of space.

To address this, some networks solve the issue for fields like addresses by placing the variable-length sub-field at the end of the table. This allows the receiver to simply read the remainder of the field without requiring padding, effectively eliminating unnecessary overhead. This method only allows a single variable length sub-field per table, however.

To address this, some networks solve the issue for fields like addresses by placing the variable-length sub-field at the end of the table. This allows the receiver to simply read the remainder of the field without requiring padding, effectively eliminating unnecessary overhead. This method only allows a single variable length sub-field per table, however.

Nibble tables

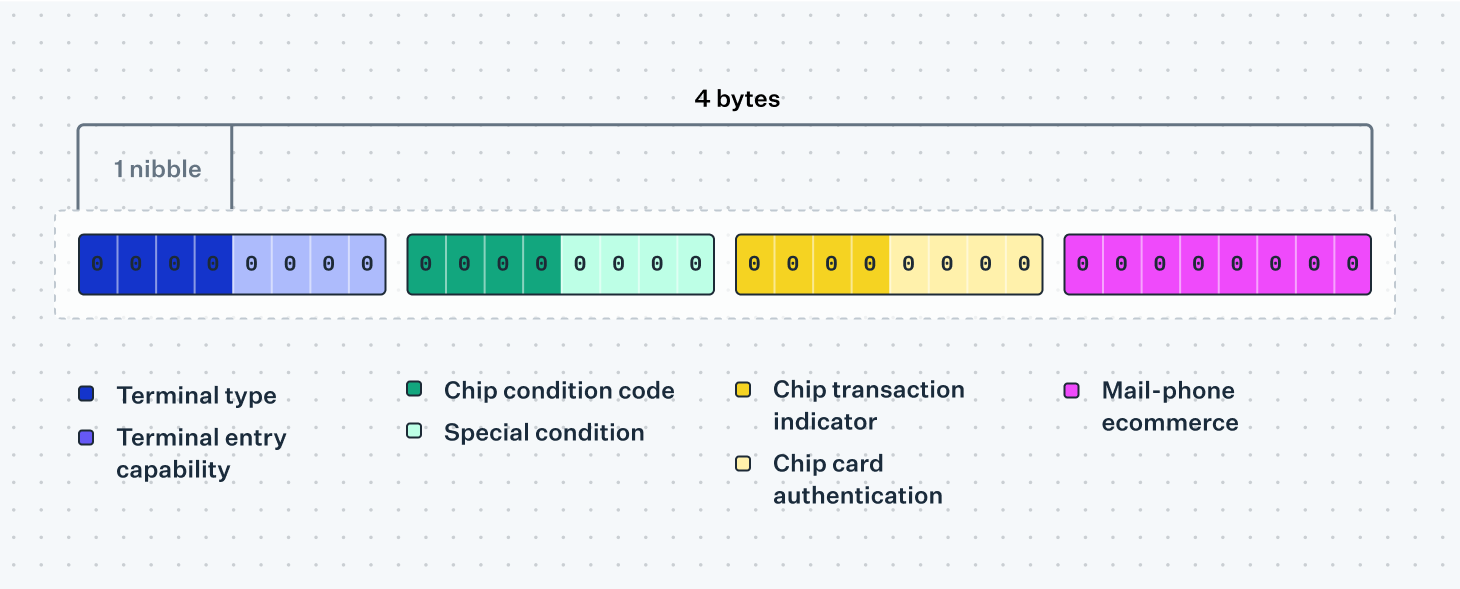

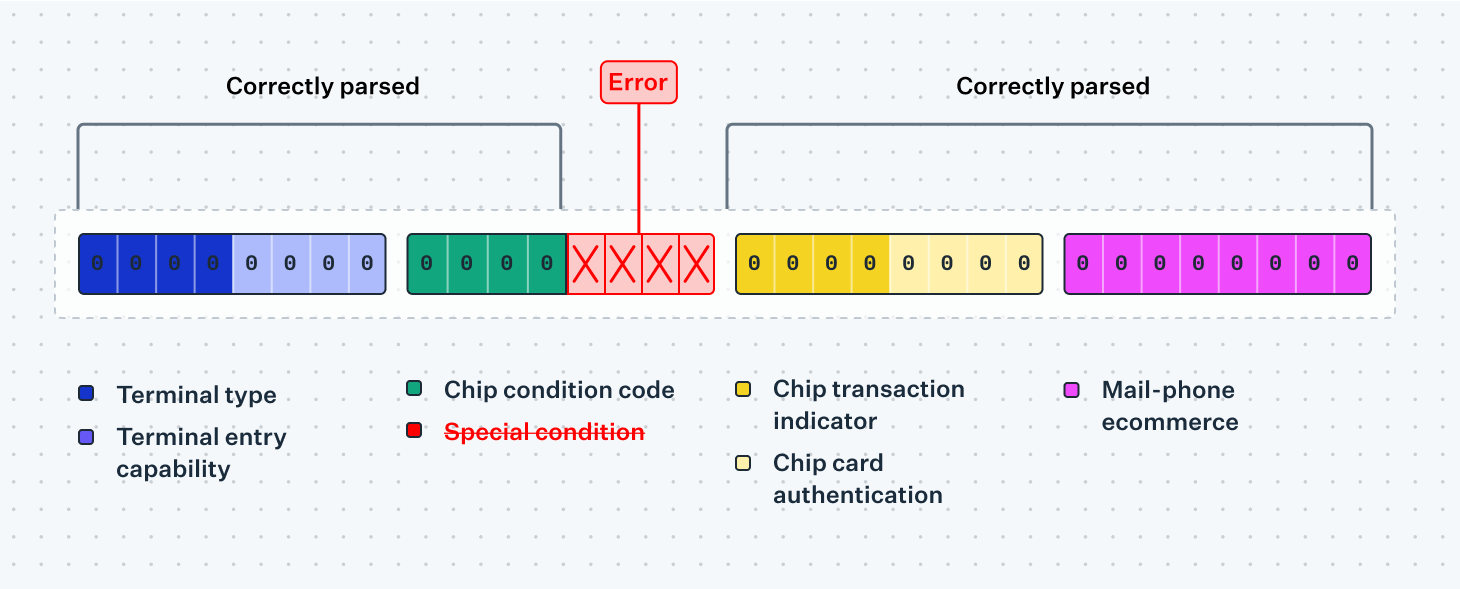

Some tables consist entirely of numeric fields encoded with packed BCD. This is the case with Visa’s Additional Point of Sale Information field, where most of the fields only consist of single-digit enums. If we were to serialize these as usual, we would end up with an entire byte for each separate field, with the first 4 bits of each byte wasted on zeros. “Obviously” an egregious inefficiency, the specification instead defines that each single-digit field should occupy only one nibble, or half a byte.

Some tables consist entirely of numeric fields encoded with packed BCD. This is the case with Visa’s Additional Point of Sale Information field, where most of the fields only consist of single-digit enums. If we were to serialize these as usual, we would end up with an entire byte for each separate field, with the first 4 bits of each byte wasted on zeros. “Obviously” an egregious inefficiency, the specification instead defines that each single-digit field should occupy only one nibble, or half a byte.

Serialized, this would look like:

- Byte 1: terminal type for the first 4 bits, terminal entry capability for the last 4 bits

- Byte 2: chip condition code for the first 4 bits, special condition indicator for the last 4

- …and so on.

Nested bitmap messages

Most of the complexity discussed earlier comes from trying to omit certain sub-fields without having to waste space on empty characters to communicate that a field has been omitted. A nested bitmap message solves this problem by including a bitmap before the elements, communicating to the recipient which fields are present and which are omitted. This is identical to how the top-level message itself is serialized, with the distinction that nested sub-level message bitmaps are generally shorter and of fixed length (e.g., 8 bytes to allow 64 bits/fields).

This is an improvement over tables in that it eliminates the need to serialize empty values entirely, saving space and simplifying the interpretation of fields. There is no ambiguity about whether an empty value indicates omission or carries an actual value (e.g., a zero amount).

It is also an improvement in retaining backward compatibility. For example, you could write a parser where you ignore any new bitmap fields that you’ve yet to implement, allowing networks to add new fields up to the maximum capacity of the bitmap (e.g., 64 fields for 8 bytes). However, this is generally not how the networks operate, as the addition of a new field is considered a significant change that requires advance notice to clients.

This is an improvement over tables in that it eliminates the need to serialize empty values entirely, saving space and simplifying the interpretation of fields. There is no ambiguity about whether an empty value indicates omission or carries an actual value (e.g., a zero amount).

It is also an improvement in retaining backward compatibility. For example, you could write a parser where you ignore any new bitmap fields that you’ve yet to implement, allowing networks to add new fields up to the maximum capacity of the bitmap (e.g., 64 fields for 8 bytes). However, this is generally not how the networks operate, as the addition of a new field is considered a significant change that requires advance notice to clients.

Tag-length value messages

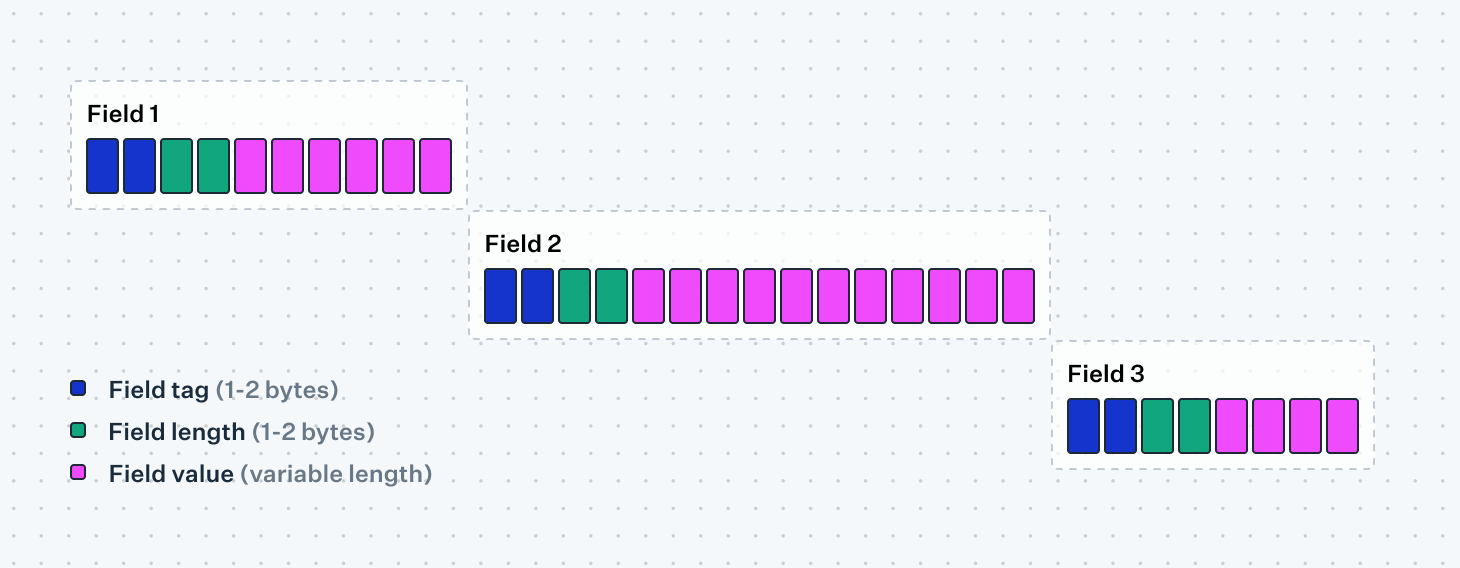

Later versions of the ISO 8583 standard incorporated parts of a separate standard altogether, ISO 8825, for use in nested sub-messages. This approach is so robust that it completely removes the need for other nested message types like tables and bitmap messages. In this format, each field is serialized as a tuple consisting of a tag, the length of the field, and the field value itself. Similar to the nested bitmap messages this lets the sender omit any missing fields as the recipient can rely on the tag component to identify which sub-field is being parsed.

The TLV format is, unlike the other two message formats we’ve looked at, unordered. While the tags are defined in a specific order in the specification, the sender can choose to serialize each tag-length-value tuple however they want without causing issues for the recipient. This would not work for the nested bitmap field, where the recipient reads the bitmap to see which fields (e.g., field 1, 3, and 5) are present and then expects the corresponding data to follow in that order. A tag-length-value parser, on the other hand, would read the tag first and use that to know which field is being parsed.

Tag-length value parsers are slightly more involved to implement but offer the most flexibility for networks: participants are expected to handle new sub-fields gracefully.

Tag and length formatting

Both the tag and length components are encoded in a way where the recipient can determine how many bytes are used for each component from the value of the initial byte. The tag, for example, only sets the last 5 bits in the first byte if a subsequent byte is necessary.

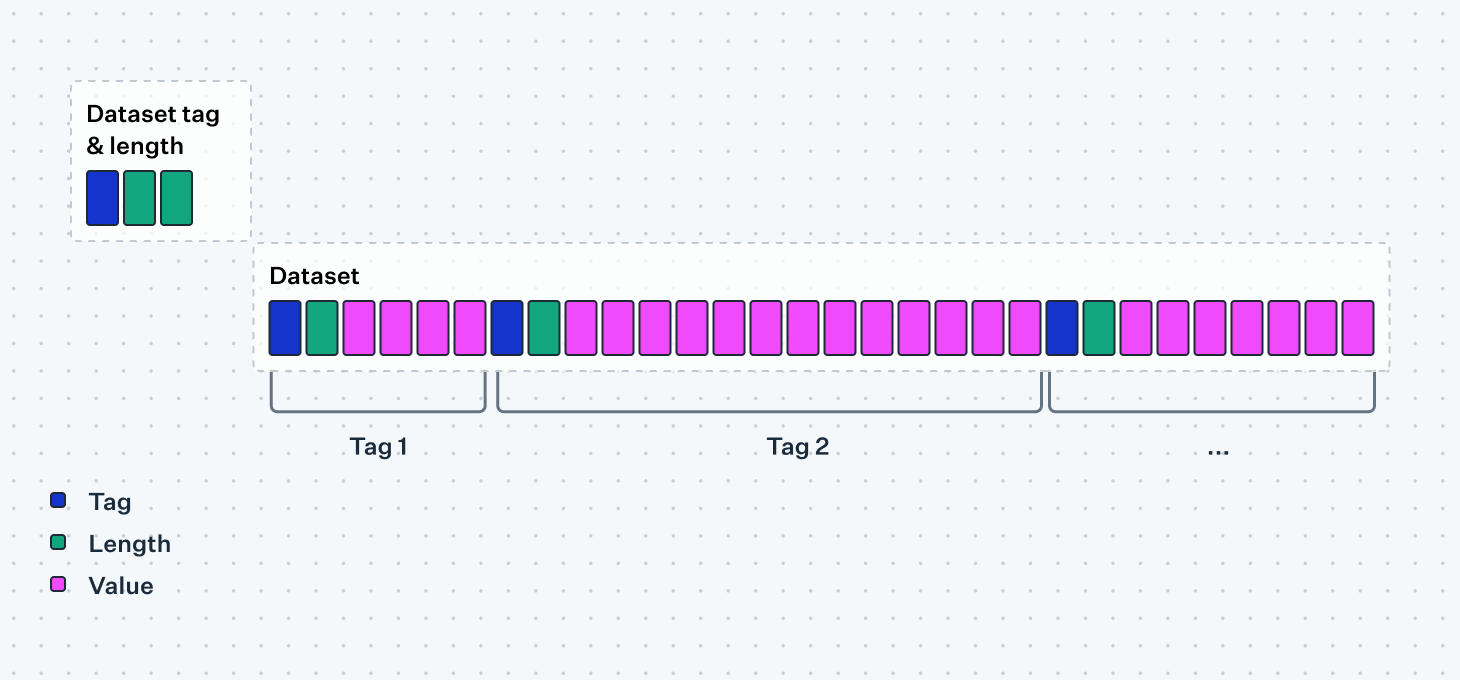

Hierarchy

Generally tag-length value messages are structured as two layers of messages: the top level is called a "dataset" where the number of bytes used by the tag and length components are fixed, while the lower level of tag-length value fields rely on the variable format for both the tag and length indicators. This provides ample room for adding more fields.

Tag-length value parsers are slightly more involved to implement but offer the most flexibility for networks: participants are expected to handle new sub-fields gracefully.

Tag and length formatting

Both the tag and length components are encoded in a way where the recipient can determine how many bytes are used for each component from the value of the initial byte. The tag, for example, only sets the last 5 bits in the first byte if a subsequent byte is necessary.

Hierarchy

Generally tag-length value messages are structured as two layers of messages: the top level is called a "dataset" where the number of bytes used by the tag and length components are fixed, while the lower level of tag-length value fields rely on the variable format for both the tag and length indicators. This provides ample room for adding more fields.

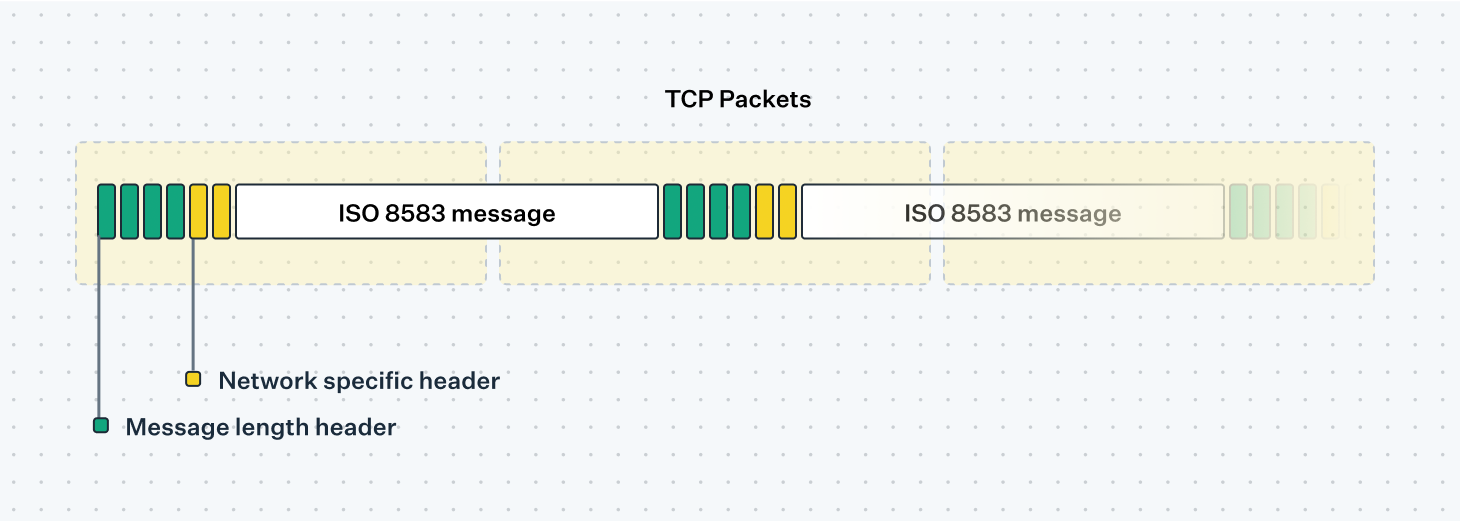

Framing

ISO 8583 messages are generally sent over long-lived TCP sockets, as described in "Visa: half a century of high availability". As such, there needs to be a layer of framing around the messages so that the recipient knows where one ISO 8583 message ends and another begins in a stream of TCP packets. This is usually done with a simple length indicator, preceding the ISO 8583 message with a 4-byte indicator that informs the recipient of how many bytes they should read for the ISO 8583 message itself.

Network-specific header

Some of the card networks, such as Visa, also include a header between the framing Message Length Header and the ISO 8583 message itself. This generally consists of meta information about the message itself, such as where it was sent from and where it is to be delivered, and whether the network rejected it with any errors.

Building parsers

Parsing a basic ISO 8583 message is straightforward and generally only requires the implementation of a bitmap parser and a length definition for each field to be able to handle the primitive elements at the top level. A lot of the complexity comes from correctly handling the various types of nested sub-messages and the subtle differences between each card network’s implementation. A useful technique for tackling this complexity is to define the core building blocks needed to declaratively compose a message, as opposed to imperatively implementing each of the different field types on their own.

At Increase we write Ruby and make heavy use of the Sorbet type system. As such we define our ISO 8583 parsers with

At Increase we write Ruby and make heavy use of the Sorbet type system. As such we define our ISO 8583 parsers with

T::Struct classes from Sorbet, which gives us a type-safe message class after parsing.This makes it easy to map from the specifications provided by the card networks to a declarative parser implementation. It is useful to try to define sane defaults—a fixed-length

Integer type is by default right-justified and padded with zeros, but if you needed to override it you could do so:Similarly, we define nested sub-messages with other

T::Structs and leave room for configuration where functionality deviates from network to network:Error handling

The

This makes graceful error handling especially crucial for issuer processors, who receive authorization requests from a large number of acquirers across the world. Failing to parse one of these messages means a decline for your cardholder, an especially frustrating experience when you’re trying to pay for a bill in person. It is also a useful concept for acquiring processors, however, where you often end up seeing incompliant sub-fields in the responses to your messages.

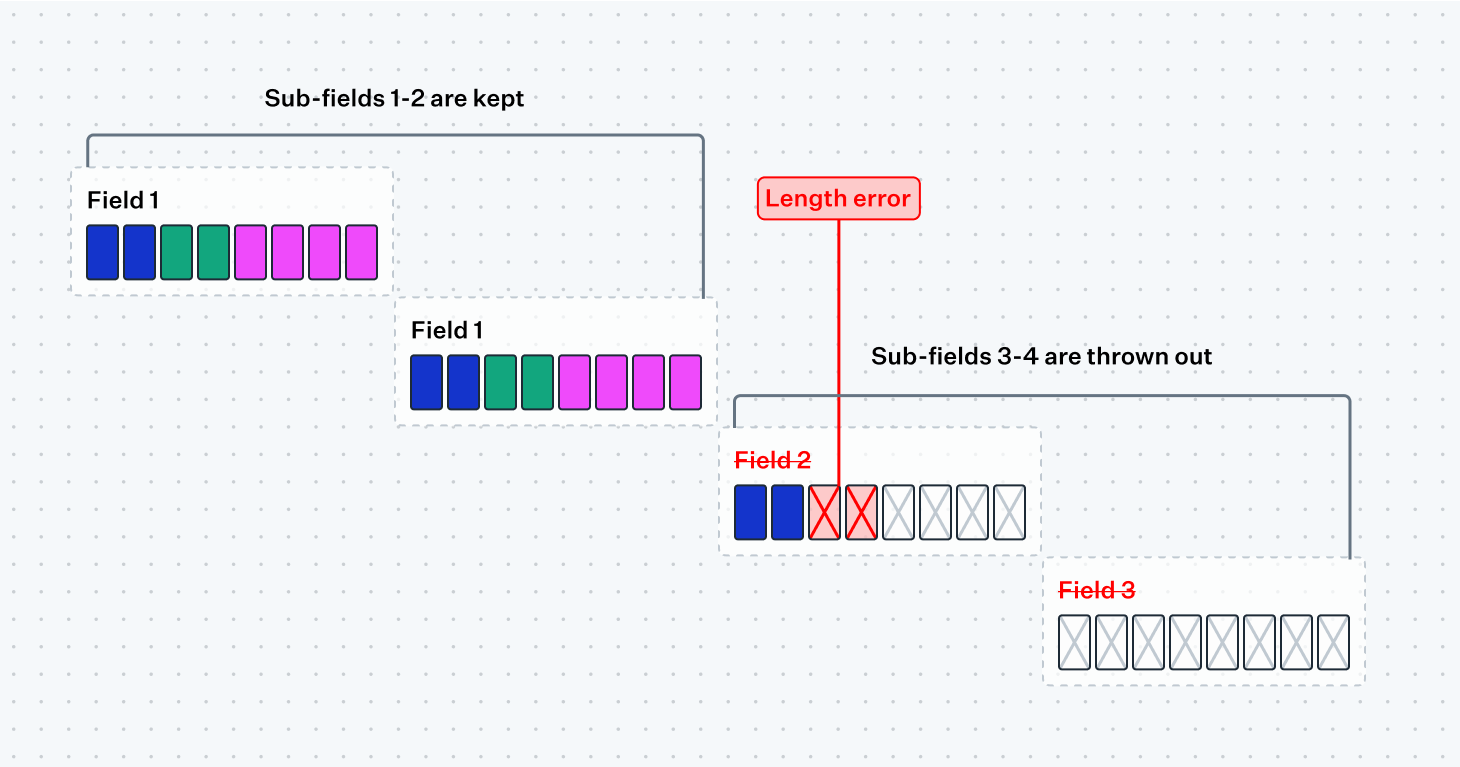

To gracefully handle errors in nested sub-fields you partition the byte stream you’re parsing such that you can continue handling the next field if an error happens in the field before. Take the Additional Point of Sale Information table from earlier as an example: each of these fields are enumerations, and you might wish to map them to an enumeration in your programming language instead of dealing with the raw network values (usually integers). If you do so you will eventually see an enumeration you have yet to handle, at which point your parser should be able to record it as a partial error and continue with the next field.

missing_tags fields in the tag-length-value messages above store a hash map of any tags we’ve yet to implement and ensure that messages still round-trip correctly without blowing up for new tags. This type of future-proofing is generally only required for tag-length-value messages, but gracefully handling local errors in sub-messages is a useful concept to apply to the rest of the parser as well. While the card networks do validate the overall format of the message, there is lots of room for subtle errors that do not result in rejections at the network level.This makes graceful error handling especially crucial for issuer processors, who receive authorization requests from a large number of acquirers across the world. Failing to parse one of these messages means a decline for your cardholder, an especially frustrating experience when you’re trying to pay for a bill in person. It is also a useful concept for acquiring processors, however, where you often end up seeing incompliant sub-fields in the responses to your messages.

To gracefully handle errors in nested sub-fields you partition the byte stream you’re parsing such that you can continue handling the next field if an error happens in the field before. Take the Additional Point of Sale Information table from earlier as an example: each of these fields are enumerations, and you might wish to map them to an enumeration in your programming language instead of dealing with the raw network values (usually integers). If you do so you will eventually see an enumeration you have yet to handle, at which point your parser should be able to record it as a partial error and continue with the next field.

An important nuance to keep in mind here is that we still need to ensure that we serialize the table back to a reasonable value (often called round-tripping), especially if it’s a table the sender expects to receive mirrored back in the response. Simply omitting the value you failed to parse altogether would result in a shorter overall length for the table, and so you'll need to either replace the unknown value with a placeholder—such as a space or a zero, depending on the content—or keep hold of the raw value you were unable to parse to put it back in the message afterwards.

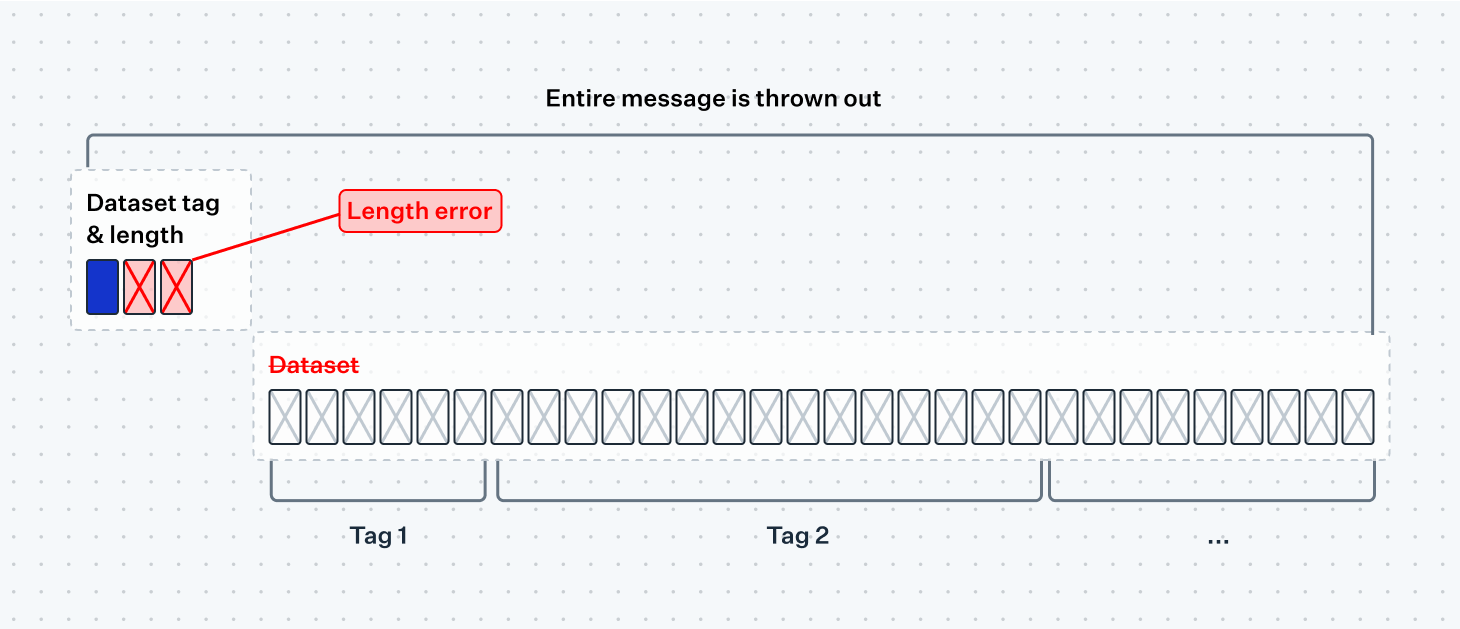

Moving up one level you can follow a similar principle for an entire sub-message itself. If we’ve parsed two fields in a tag-length-value message correctly but then reach an error trying to interpret the length indicator of the next tag, we’ll need to throw out the rest of the sub-message and keep what we parsed so far, even if it means potentially throwing away sub-fields that would've followed after the faulty length indicator.

Moving up one level you can follow a similar principle for an entire sub-message itself. If we’ve parsed two fields in a tag-length-value message correctly but then reach an error trying to interpret the length indicator of the next tag, we’ll need to throw out the rest of the sub-message and keep what we parsed so far, even if it means potentially throwing away sub-fields that would've followed after the faulty length indicator.

Finally, at the very top level there are errors that we just can’t recover from. If we fail to parse the length indicator for one of the top-level fields we’ll have no way to parse the rest of the message and it is likely critical enough that we shouldn’t attempt to use what we have so far. This is the type of decision you want to make for every part of your parser that can possibly fail—have we reached a fatal point of no return or is there a way we can gracefully continue to parse the rest of the message, despite the error we just experienced?

Conclusion

Throughout this article we’ve looked at some of the interesting intricacies that arise when parsing ISO 8583 messages, and discussed how they came to be from the initial ISO 8583 standard defined in 1987. When you use Increase for Programmatic Card Processing we take care of parsing the card network messages for you so that you can focus on building your product. We do so in a way that avoids hiding or obfuscating details, as described in our "No Abstractions: an Increase API design principle” blog post. If this approach resonates with you, contact our sales team to talk about using Increase as your issuer processor, or check out our API documentation.

[0] Card Acceptor is usually synonymous with merchant: an entity that accepts cards for payments.

Martin Ek

Engineering

Increase is not a bank. Banking products and services are offered by Grasshopper Bank, N.A., Member FDIC, First Internet Bank of Indiana, Member FDIC, and Core Bank, Member FDIC. Cards Issued by First Internet Bank of Indiana, pursuant to a license from Visa Inc. Deposits are insured by the FDIC up to the maximum allowed by law through Grasshopper Bank, N.A., Member FDIC, First Internet Bank of Indiana, Member FDIC, and Core Bank, Member FDIC. FDIC deposit insurance only covers the failure of the FDIC insured bank.